Why I'm Happy Every Father's Day, Long After My Dad's Been Gone

There’s a conversation I’ve had a few times in recent weeks - both with people I’ve just met and people I’ve known for a little while. It often comes up because we get into the topic of my mother being from Malaysia, then they’ll ask where my dad is from and if my parents live in London.

That's my dad on the left, and Mama on the right

When I reply that my mother is still in England and that my dad passed away a few years ago, it’s always met with these deeply sad eyes: the same eyes I give when someone tells me that one of their loved ones has passed. Your whole body turns to empathy; you know there’s nothing you can do to help this person’s situation and you’re not sure whether to move swiftly on with the conversation or whether to take this time to understand more about the circumstances instead of tiptoeing around it and perhaps wondering what happened for years to come.

As soon as I receive those sad eyes, I like to take the opportunity to explain why I’m very deeply happy with my father’s death. My first words are always “But it’s okay! We were really close.” and then, knowing that sounds contradictory (surely if you were close, it’s harder to deal with?), I go on to describe the lesson I learned from his death and how I apply what I’ve learned to my relationships with people now.

They might not even want to hear it, but it’s one of my favourite things to share so I tell them anyway. Luckily, if you don’t want to hear it, you can stop right here and head back to Facebook :))))

So my father died of a subarachnoid haemorrhage in December 2009, a couple of weeks before Christmas. He had been struggling with liver cirrhosis among other things that it’s not important here to go into. He had a bleed on his brain and we got a call in the early hours of the morning saying they might be able to operate. We got a call back around 5:30am saying he’d gone. He was 53.

He was staying in Devon and my mother and I were in Essex, by the seaside, at our (and his) home. I was seventeen and in college.

My grandad (my father’s father, he’s our rock, hey Grandad if you’re reading this!) drove my mother and I quite silently down to Devon, where we met my brother and my dad’s brothers. You go through the motions with such high adrenaline that it feels like nothing at all.

Grandad, Dad, my brother and cousin

We spent the next couple of weeks arranging the funeral - it was two weeks later having had the post mortem, and we cremated my dad on December 21st. A couple of years earlier he’d written me a note that ended “Never cry for me again”, so I made sure I went through that day without shedding a tear. It was much easier than I’d thought, having this big cloak of warmth around me the whole time from knowing what a complete relationship we’d had, and how I got this cloak of warmth is what I’d like to share with you.

My father and I were best friends. I used to follow him around the house and he’d call me his ‘shadow’, sitting in his office for hours, him explaining the world to me and me asking endless questions and pressing flowers and clovers into his big books. He taught me how to tie my shoelaces; he taught me about periods, boys, how to do a flaming Sambuca. He taught me that, as I went through teenagehood, I’d loathe him and distance myself and that I’d come out the other end and we’d be best mates again. I did spend small amounts of time rolling my eyes and cutting off his questions with one-word answers and closed doors, but there was something in knowing the process that meant we were always close underneath it all.

The reason I’m happy with his death - not with him dying, of course, but with his death - is that there was nothing left unsaid. There are things I never shared that I would tell him now as an adult, but it wasn’t the right time to tell him them as a teenager (he’d probably have killed some young men). There are no regrets; there’s no heaviness.

I’ve come to learn - and studying yogic philosophy & advaita actually really helped put this into words! - that there is a difference between pain and suffering. Grief is a physiological thing that we go through when someone we love dies. It’s a tightness of the chest, a hollow heaving that smacks down on the stomach - and it can come at any time, not just in the weeks or months following death. Suffering, on the other hand, is knowing that we should have acted, but we didn’t. Or that we shouldn’t have acted in such a way, but we did and we never put it right.

Suffering stems from regret - we crave a different past because we didn’t follow the right path at the time. It takes time to let that go, and self-forgiveness. (Whatever the situation, you deserve self-forgiveness.)

The lesson I learned from my father’s death was that we should give our all to every relationship without expectation. Never going to bed without making peace or at least reaching out and trying.

I would have learned this lesson either way, and I feel extremely lucky to have learned it in the form of “Everything with Dad’s death was great because I put all I could into the relationship when he was alive, and so I should make sure I act in the same way with others so that I feel this clear when their deaths come”. The other way I could have learned it was, “Everything with Dad’s death was awful because I didn’t see him enough/forgive him/stand by him, and so I should act differently with others so I avoid feeling this terrible when their deaths come”.

I guess that’s what pressed me to write this post: if you haven’t already experienced the death of a loved one, you don’t have to learn this lesson the hard way. And you don’t have to learn it by reading a sad story. I’m writing this now from a place of deep clarity, from a comfort that will be with me till my own death. Know that people you love will inevitably die. Know that it’s okay! Although you will experience grief, you don’t have to experience suffering.

This isn’t to say that I don’t miss my dad - I miss singing with him while he plays guitar and I miss the winks he would give me whose meaning I could never put into words. It’s that the ‘missing him’ is carried with a smile, with the knowledge that a seventeen-and-a-half-year perfect relationship isn’t ‘cut short’. It’s complete and filled with a level of quality that no number of years can guarantee.

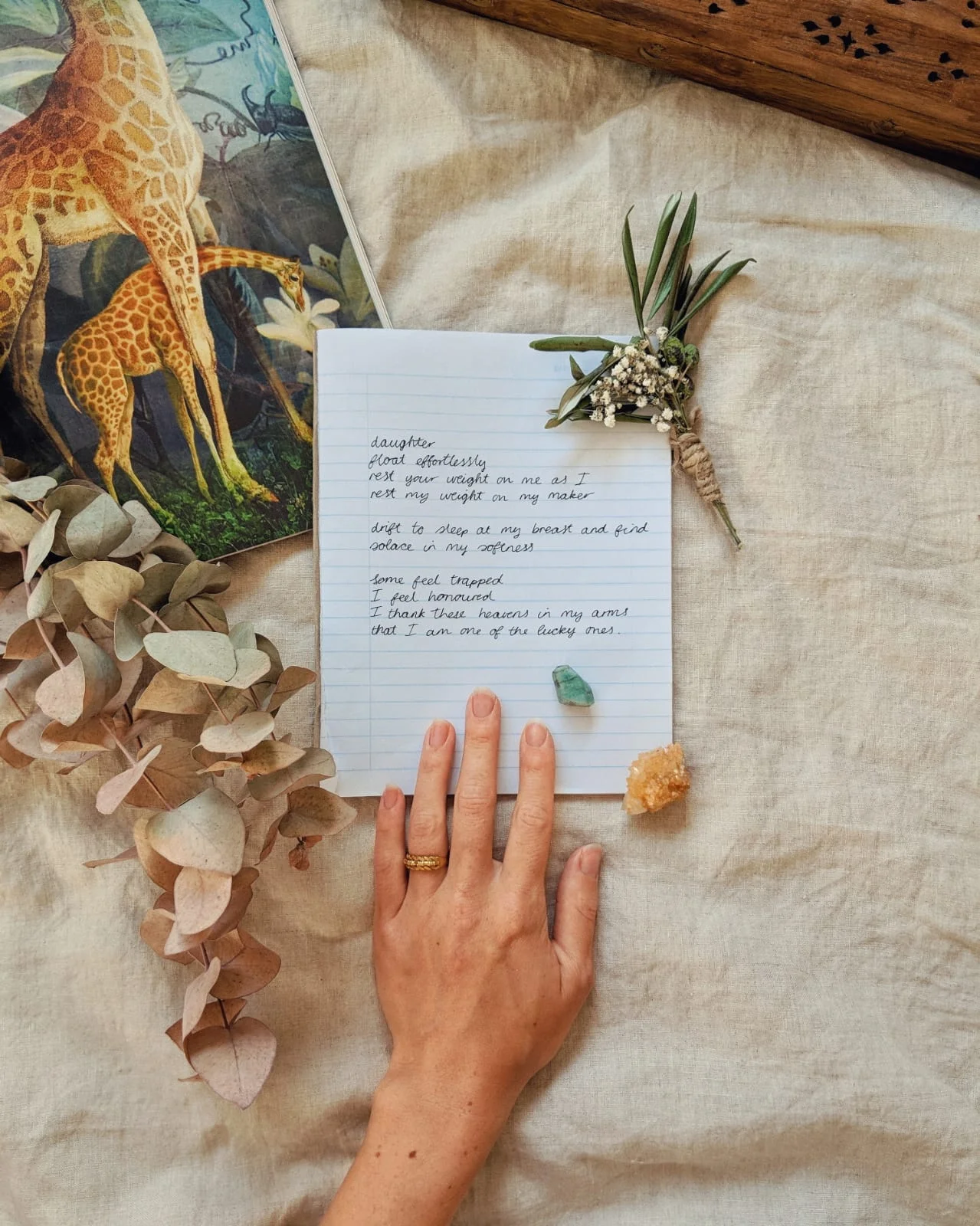

I wrote this spontaneously so don't have any recent photos to hand :)

This also isn’t to say that, for example, if your mother left you as a teenager and you’ve written to her ten times with no response, you should continue writing to her each year because you’re scared of regret. This is about your judgement and your own conscience: your gut feeling about how you’ve acted towards another person will tell you everything you need to know. It’s about going to bed knowing you’ve done your part.

It’s like Chris (Simpsons Artist) says: If you love someone, just tell them. If you feel sick, just be sick.

We’re formed as these adults with faces that block our souls from spilling out where they’re meant to be. So I guess this is my ask of you: give everything you can to your father if he’s around this Father’s Day. If he’s not, and you’re cool with it, then great. If he’s not, and you’re suffering, forgive yourself. And then do the same with everyone you know. Not on my behalf - not because I’m sad that my dad isn’t around for me to give some love - but because I gave him all the love I could and I know how good that feels. I can’t touch the weird mole on the side of his head with my fingers, but I can connect to a love so deep and pure that it doesn’t matter whether he’s dead or alive.

You have the power to create that, and I invite you to join me in doing so.

Thanks for reading! :)

Serena

Dad, my brother, Ah Kong (mum's dad) and me in Muar. I'm wearing my lycra Union Jack Spice Girls crop top and I wish I could still fit into it now